Mobile Money: Understanding and Predicting its Adoption and Use in a Developing Economy

During my summer internship at Vodafone Research, London, I had the possibility to work on the interesting topic of mobile money, that led to our recently published paper called “Mobile Money: Understanding and Predicting its Adoption and Use in a Developing Economy”. [full_paper]

Mobile Money

What is a mobile money service? Why is it needed? As of today, there are approximately 2 billion unbanked individuals worldwide1, adults who are not bank account holders or do not have access to a financial institution. Access to financial institutions is difficult in developing economies and especially for the poor, due to the low penetration of financial services in such countries, particularly in rural areas. The widespread adoption of mobile phones, including in developing countries, has enabled the rise of mobile money services. Mobile money bridges the gap between the cash and digital economies, enabling those without access to banks to load cash in a mobile wallet and transact digitally using money transfers, deposits and withdrawals of money, bill payments, etc. through the mobile phone network.

M-Pesa

In 2007, the largest mobile operator in Kenya, Safaricom (owned partially by Vodafone) launched a new payment and money transfer service delivered through its mobile phone network, known as M-Pesa. M-Pesa stands for Mobile “Pesa”, the Swahili word for money and it is the world’s most successful mobile money service.

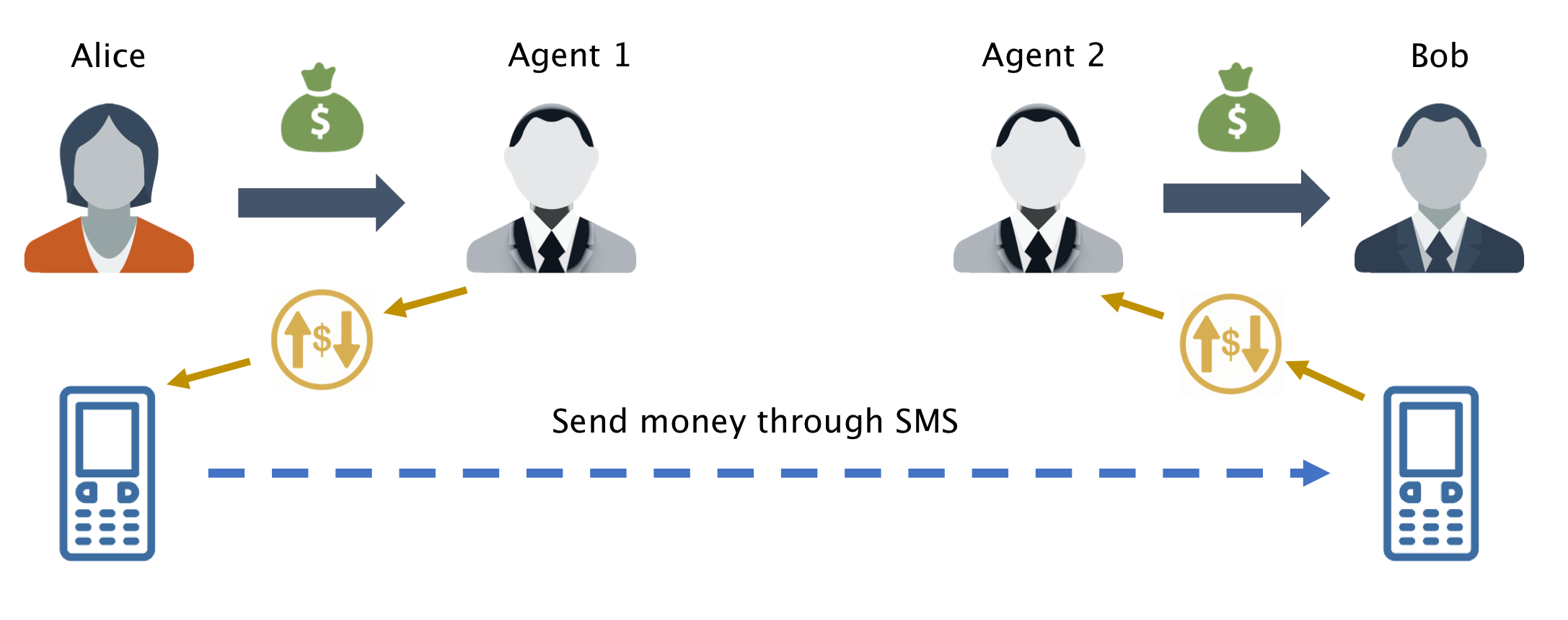

After a simple registration phase, requiring an official form of identification, the service allows its customers to perform a variety of services, including deposit money on their M-Pesa account associated with their mobile phone; transfer money via an SMS to another mobile phone user; withdraw cash from their M-Pesa account; purchase airtime and pay bills. To enable money deposits and withdrawals, M-Pesa runs and maintains an extensive agent network distributed on the territory. In fact, M-Pesa acts as a branch-less banking service where the “ATMs” are replaced by agents, which generally consist of already existing airtime resellers and retail outlets. An example of a money transfer between two M-Pesa customers is depicted in Fig 1.

Fig 1. Suppose Alice and Bob live far from each other and that Alice wants to send money to Bob in a fast and secure way. (1) Alice goes to the M-Pesa agent (Agent 1) and (2) top up her M-Pesa account. Then (3) Alice sends the money to Bob with a specific SMS. (4) Bob can go to the nearest M-Pesa agent (Agent 2) and withdraw the money from his account.

As of today, M-Pesa has grown rapidly and the service is offered in 8 countries: the Democratic Republic of Congo, Egypt, Ghana, India, Kenya, Lesotho, Mozambique and Tanzania.

Mobile Money adoption and use

In this work we were mainly interested in understanding whether and to which degree past mobile phone usage captures elements of human behavior that are predictive of future mobile money usage.

In order to answer this question we used two datasets containing mobile phone communications and mobile money transactions of an African country from two different time periods. The first dataset, D1, contains pseudo-anonymized Call Detail Records (CDRs) of a random sample of 100,000 customers during a three month period from November 2016 to January 2017 (T1). In total, dataset D1 has more than 140 million CDR events. The second dataset, D2, contains M-Pesa transactions, from April 2017 to June 2017 (T2), for a total of more than 1.2 million randomly selected customers (including the customers in D1) who generated approximately 27 million M-Pesa financial transactions.

We then used this data to build two machine learning-based predictive models that predict future M-Pesa adoption and intensity of usage, using multiple sources of data, including mobile phone data, M-Pesa agent information, the number of M-Pesa friends in the user’s social network, and the type of geographic location where the mobile activity took place.

Feature extraction

We devise a set of features that allow us to capture a fairly comprehensive picture of a customer’s behavior which we then use as input to two machine learning-based models to predict future M-Pesa adoption and intensity of usage. The main families of features we extracted are the following:

- Mobile usage: features that describe the mobile phone usage of the customers

- e.g. active days, number of calls, percentage of nocturnal calls, etc.

- Mobility: gives information about a customer mobility

- e.g. number of visited antennas, number of visited districts, radius of gyration, etc.

- Agent network: information about the location of the M-Pesa agents

- number of agents in a 500m radius, minimum distance to an agent

- Ego network: features that describe the social network of a customer

- e.g. degree, number of M-Pesa friends, percentage of M-Pesa friends

- Location characterization: home and work location characterization

- rural/suburban/urban

Predicting M-Pesa usage and spending

Our two datasets D1 and D2 were collected in different time periods: the dataset D1 from November 2016 to January 2017 (T1), and the dataset D2, three months later, from April 2017 to June 2017 (T2). Hence, we computed 77 features using the data in D1 and then defined our M-Pesa target variables using the data in D2. With this setting, we are able to investigate whether and how past mobile phone behavior, as captured by features from D1, is related to the future usage of M-Pesa, as captured by M-Pesa-based target variables defined in D2.

-

Task 1: Predicting M-Pesa future usage. In this classification task we are interested in identifying users who are inactive in T1 but will be active in T2. While all the customers in the dataset D1 are registered M-Pesa users, only a fraction are active customers. We define a customer as active if (s)he has carried out at least one M-Pesa transaction in dataset D2. We randomly split the set of customers in 80% for the training set and 20% for the test set. We then used a Gradient Boosted Trees (GBT) model that reported an AUC score of 0.691 from 5-fold cross-validation. This result is comparable to previous work2, even if we are predicting M-Pesa usage 3 months into the future.

-

Task 2: Predicting M-Pesa future spending. In this second classification task, we investigated whether the customers’ past mobile communication behavior is related to their future mobile money spending behavior. Focusing on the customers for which we have M-Pesa transaction data in D2, we computed the total amount of money spent in the three month period under evaluation. Then, we created two classes of low and high spending customers by selecting the customers falling in the 25th and the 75th percentiles respectively. We then randomly split the set of customers in 80% for the training set and 20% for the test set. Before testing the classifiers and given the sample and feature sizes, we applied a feature selection step in order to reduce the dimensionality of the feature space, lowering the risk of overfitting. In this case, we report the results of a Support Vector Machine with RBF kernel and standardized features (z-score). We obtain an AUC value of 0.619, which is the average value across test sets from 5-fold cross-validation. Changing the percentile split for high and low spenders it is possible to reach a 0.715 AUC score depending on business needs.

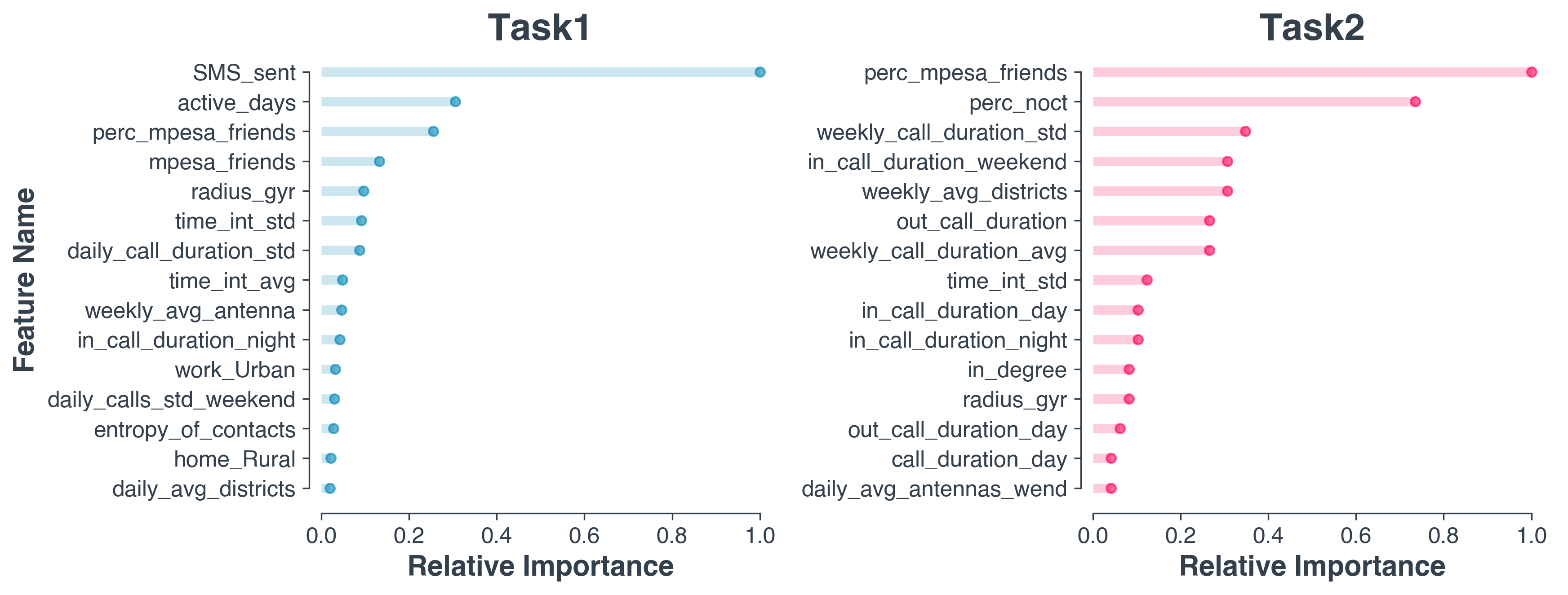

The most important features for the two classification tasks are shown in Fig 2. (If you are interested in generating the barplot as in figure, you can find here a tutorial).

Fig 2. Feature importance in Task 1: predicting M-Pesa usage (left), and feature importance in Task 2: predicting M-Pesa expenditure (right).

Main results

Despite the limitations of our dataset, represented by the random sample of customers and a 3 month gap between the two datasets, we found some interesting insights:

-

The most predictive features are related to mobile phone activity (e.g. SMS_sent, active_days) and to the presence of M-Pesa users in a customer’s ego-network. Thus, we observe a relevant level of social virality in the likelihood of using M-Pesa, as also reported in another work on mobile money 3. Moreover, the mobility of a customer is a non-negligible predictor as shown by the radius of gyration.

-

Surprisingly, in the top 15 most predictive features of our models, we did not find features related to the distance and density of agents.

-

Our findings and models also have business value as they enable mobile money service providers to better identify potential new customers of their services, anticipate consumption and understand the key drivers for mobile money adoption and usage.

You can find all the details and the complete results in the full paper, together with some descriptive analysis on the M-Pesa transactions and a deeper discussion on the feature analysis.

-

http://www.worldbank.org/en/programs/globalfindex ↩

-

Khan, M.R., Blumenstock, J.E. “Predictors without borders: behavioral modeling of product adoption in three developing countries.” In Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining (2016): 145-154 ↩

-

CGAP. “The power of social networks to drive mobile money adoption.” Technical report (2013) ↩